Epiphany: The Light of Christ Revealed

Even after we celebrate Christmas Eve and Christmas Day with stockings, gifts, and more food than we should have eaten, we must not quickly put everything away and move on to the New Year. Advent and Christmas cannot be over. Advent and Christmas are only the beginning of the story, not the end. Their messages are meant to shape us all year long.

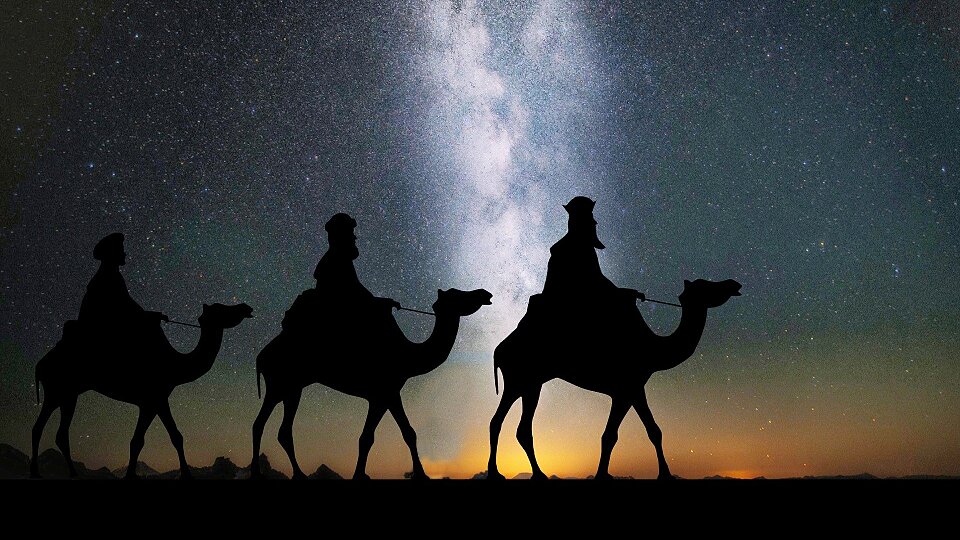

Thirteen days after Christmas comes the feast or celebration of Epiphany. For Christians in the west, Epiphany is January 6. The word itself means to appear or to be seen or manifest. Epiphany represents God revealing his light and presence through Jesus to the world, with a particular emphasis on the Gentile world. The story of the magi is the archetypal story of God beckoning Gentiles to himself. On Epiphany, Christians also remember the story of Jesus’s baptism at the age of thirty, during which the Spirit descended upon Jesus as a dove. God the Father spoke from heaven saying, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” (Mark 9:7).

The magi bowing before the infant Christ, and the voice of the Father announcing that Jesus is his beloved Son, calling us to “listen to him,” leads to one final word given in the Christmas story that I’d end our study with. This title was the essential affirmation of early Christians, so that Paul could say that if an individual professed this of Jesus, and believed in Christ’s resurrection, they were saved. It is this title that captures the essential relationship Christians have with Jesus. What is that word? Listen again to the words of the angel to the night shift shepherds that first Christmas: “I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord” (Luke 2:10-11, italics added).

He is the Lord, but is He Your Lord?

No other title is used more frequently for Jesus by the early church, and in the New Testament, than Lord. It appears over six hundred times in the New Testament with reference to Jesus (and over a hundred other times more broadly to refer to God, and at times simply as a title of respect addressing individuals). The earliest Christian creed was simply the phrase, “Jesus is Lord.” Paul writes in Romans 10:9, “If you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” And in 1 Corinthians 12:3 he writes, “No one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except by the Holy Spirit.”

The English word lord signifies someone in authority, typically the highest person in authority in a given realm—whether in the house, the community, or the nation. It comes from the Old English hlaford or hlafweard—loaf-warden, eventually shortened to lo-ard and then lord. It meant the “keeper of the loaf,” the person who protected and held authority to determine the distribution of the bread or the resources of the family, community, or realm. The loaf-warden was the title of the person “in charge.” By the way, the term lady comes from the Old English hladige, which meant loaf-kneader, the person who made the bread. In the patriarchal world of the past, lord and lady were terms that described authority and function in a home or community.

It is no accident that Luke begins his telling of the Christmas story by saying, “In those days Caesar Augustus...” (Luke 2:1 CEB). It would seem that Luke wants us to make the connection and to see the contrast between Caesar and Christ. Caesar commands a census that forces the Holy Family to travel to Bethlehem. Mary gives birth in a stable among the animals—essentially homeless—with an animal’s feeding trough as Jesus’s bed. This is as humble and lowly a birth as one can imagine in the first century. In the Empire, Caesar is “Lord.” But the angel came announcing to the night shift shepherds, as we’ve read already, “I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord” (emphasis added).

We’ve learned that the word messiah means “anointed one” and is essentially another word for king. This child whose birth the angels announced was both king and lord. But he is not just a lord. He is not simply a local king serving under the auspices of the emperor as King Herod was. The angels were announcing that Jesus was the Lord, or as Revelation describes him, “Lord of lords and King of kings” (Revelation 17:14 and 19:16).

As the early Christians said “Jesus is Lord,” they were saying several things. They were saying “Jesus is the highest authority in my life. He is my Master, Sovereign, Ruler, Commander, and King.” Lord was not simply a name they used to address Jesus; it was a title that reflected their submission to his will. When we begin our prayers, “Lord...” we are acknowledging his authority in our lives. We are yielding our lives, our hearts, and our wills to his will.

I’d like to invite you to consider this when you pray. When you address Jesus as Lord, you are acknowledging his authority. You are recognizing that you belong to him. You are expressing your relationship to him. You are yielding your life to him. To be a Christian is not only to say, but to live the words, Jesus is Lord.